Foreword

I want to tell you a story. It’s a story of a grand adventure. In this story there was a crime committed. I’m sitting at my desk. My nice, wooden, solid, don’t-make-them-like-that-anymore desk. I’ve gathered my crayons and markers, and I’m going to draw this adventure for you.

Do you have a story? An adventure? A wild tale? Why don’t you write the story and then draw it. That’s how I did it.

So sit back and relax, and let me tell you a story about the hunter, a black hound dog who would be king of the wild.

The red station wagon stopped underneath the aqueduct. Five boys, including me, jumped from the Ford and raced for the back door of the wagon.

The brown man nonchalantly walked to the back of the vehicle. He was my father. He knew we were excited, so he stopped, lifted his arms skyward and stretched as if he had just driven across the country. He exhaled in a mighty drawn-out sigh.

We shuffled nervously and eyed him impatiently. All eyes were on his hand when he finally fished the key from his pocket and placed it into the key slot. He opened the door, and we rushed to our backpacks and sleeping bags. We hurled insults at each other as we pushed and shoved and punched.

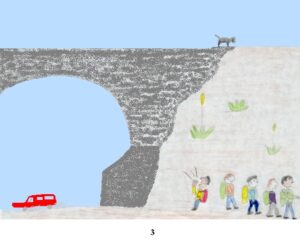

We hoisted our packs onto our backs and took off at a fast walk into the desert.

I yelled for my dog.

“Cassius! Here boy. C’mon boy.”

That brought the black hound away from the edge of the canal that ran within the aqueduct. He looked down from his lofty height above the desert floor and then sprinted after us as we moved away from him, heading into the wilderness.

The dog ran down the embankment, his ears pinned to his neck. He soon caught us. Cassius had looked down upon the countryside from the height of the aqueduct. He liked what he saw. With a sniff and then a lift of his leg, he claimed the land as his domain.

The dog scouted the land. He ran in a big semi-circle as he sniffed the ground. He was a hound. He was a hunter. If there were animals lurking in the wild, the hound’s superior nose would find them.

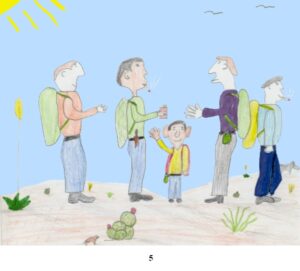

We hiked into a gully and walked it for a while before we scrambled out the other side of the ravine. My brother Joe stopped and pulled out a pack of cigarettes from his backpack and passed it around.

The older boys lit up and smoked. And why not? We were free now. There were no parents to order us around. There were no adults to ruin our fun.

I pretended to want a cigarette, but I was ignored.

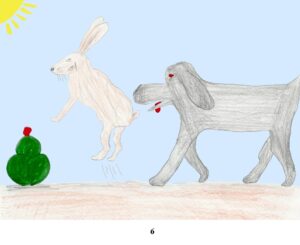

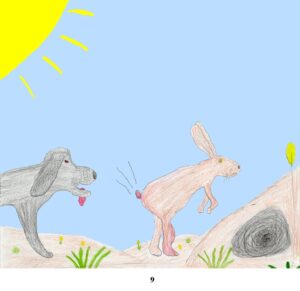

It wasn’t long before the hunter found a jackrabbit. The rabbit tore out in terror as the dog chased him across the hard desert ground.

They ran, the jackrabbit using the cactus, creosote and yucca as obstacles against the dog. The rabbit zigged and zagged and dodged here and there, but the dog wouldn’t give up the chase.

The hound barked and harassed the jackrabbit and nipped at his heels. We could see the big hare’s bobbing ears in the distance, when suddenly, the rabbit, bobbing ears and all, disappeared as if magic.

Cassius angrily barked at the hole into which the swift rabbit vanished. The hunter noisily challenged the animal to come out, but the rabbit refused to let the dog’s belligerence provoke him into being stupid. He stayed in his hole.

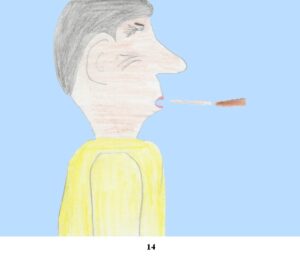

The guys started on the second round of cigarettes, lighting them in a more expert fashion than before. Joe offered me a “cig,” and even though I didn’t want it, he was my big brother. It was because of him that I was on the hike.

So I took the cigarette and lit it, though it took me five matches. The smoke made my eyes water, and I almost choked when I inhaled. I kept smoking though, but without inhaling, hoping to impress the older boys.

But then I got a headache. I could feel my body warn “DON’T SMOKE IDIOT!” and I had to agree with it. When no one was watching, I threw the half-smoked cigarette away.

The dog disappeared into the desert for a spell, and then he reappeared. He smelled odors that he had never smelled. Wild odors. He was thrilled.

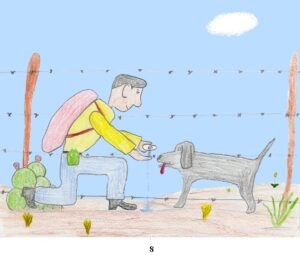

He was thirsty.

His tongue hung out, and with exaggerated pants he pretended to be sorely dehydrated. I pulled my Army canteen from its holster attached to my belt. I used my hand as a cup and poured water for the dog to drink. Cassius licked the water greedily.

Without so much as a look of gratitude for the water, the dog ran off, his nose vacuuming desert scents off the ground, the greasy bushes, the occasional scrub tree.

He found another large rabbit. This hare had an irritated rash on his butt and right leg, so the dog didn’t really want to catch him, but he chased him for fun. The resemblance of the dog to the coyote was not lost on the frantic rabbit, who thought the dog must be the sly coyote’s cousin on vacation.

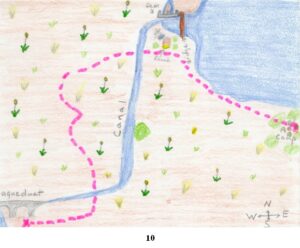

We started the hike at The Flumes where the mighty aqueduct spanned the Pecos River. We walked across the desert toward Lake Avalon, where we camped for the next two days. We climbed fences. We navigated a maze of gullies. We threw rocks.

We reached the ranch house, whose owner guarded the lake’s bridge and dam, and we drank water from his well. Then it was on to the lake.

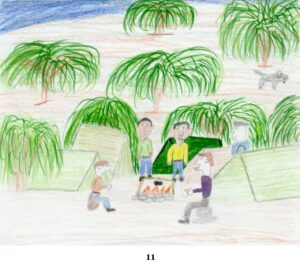

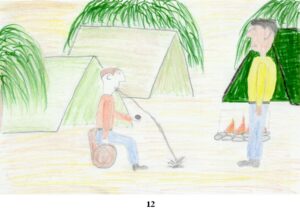

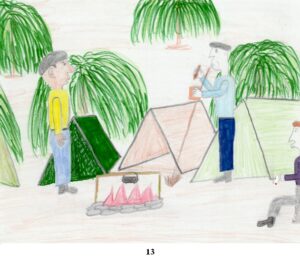

We skirted the lake until we came to a grove. We set up our camp. The dog ran to a spreading salt cedar and rested beneath its boughs, but only momentarily, because he couldn’t relax. His elation with being free was just too great. He confidently ran out of the camp in a new search of prey. Meanwhile, we pitched our tents and built a fire.

Once our sleeping bags were unfolded in our tents, the hike was officially over.

John pulled a can of snuff from his pocket and offered it around.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“It’s smokeless tobacco. Snuff. Instead of smoking it, you put it between your lip and gum like this.” He stuck his finger into the can, scooped up some black, worm-dirt looking stuff and stuck it into the inside of his lower lip.

“That’s it?” I asked.

“Yea. But you don’t swallow it. You spit out the juice.”

He let loose a long stream of black disgusting spit. He cleaned the dribble from under his bottom lip.

“Naw,” offered David, whose brother was Denis. “Try this.” And he indicated that I should take a packet of long stringy tobacco from his hand.

“What’s that?” I asked. Obviously, I didn’t know much.

“It’s chewing tobacco. Look, just grab a wad like this, and stick it inside your cheek like this. You can chew on it and then spit.”

David let go with what appeared to be brown unhealthy phlegm.

It was disgusting.

I was impressed.

“I’ll try the chewing tobacco,” I bravely offered. “At least you chew it, not like that other stuff that just sits there.”

I really didn’t want tobacco in any form, but I took the packet anyway. I pulled out a wad of the sticky brown leaf and lodged it between my teeth and cheek. I chewed and sucked and chewed and sucked some more.

“Oh no,” I groaned softly, and then I spit.

“Phhhhpppppttttt!”

Talk about impressive. With tremendous force, my mouth propelled a spiraling wad of tobacco wrapped tightly in brown saliva across the camp. The soft leafy missile hit the ground beyond the fire.

“That stuff tastes terrible,” I whined. The guys laughed at me and called me derogatory names I cannot repeat here.

“Give me that other stuff. I’d rather do that,” I stupidly said, trying desperately to save face. I didn’t want them to think I was a wimp, so I took a finger full of snuff like John had done, and I stuffed it behind my lower lip.

‘YUCK!’ I thought. But I didn’t dare say it lest the guys consider me a weenie. So I sat there and sucked and spit and sucked and spat.

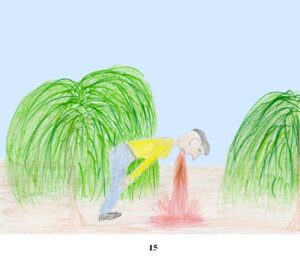

It wasn’t long before I began to feel the spin of the earth, and I realized I was about to be ill. I ran several feet from camp before I threw up with a violent BBRRrrrraaaaLLLLPPPHHHHhhhh!! over and over again.

The guys laughed at me, and my brother called me a weenie. I had proved nothing except that I was a moron. I was an idiot. An idiot with vomit on my breath and boots.

I crawled into my tent and prayed the nausea would go away. The dog came into camp and found me. He sniffed my face, and then with a nose wrinkled in disgust, he ran off. He obviously disapproved of my actions.

Maybe a walk would make me feel better, I reasoned.

“Cassius!” I yelled as I stumbled from the tent. The black dog came out of the trees, his tail a banner in the air.

“Let’s go boy,” I called. I walked down a path that split the salt cedar grove. Cassius ran among the trees sniffing suspiciously at unfamiliar smells.

I began to feel better, but the sickening effects of the tobacco wore off slowly, and I was queasy for another hour. I could see the lake’s water beyond the trees, so I turned off the trail and headed toward the lake.

Cassius sensed my move, and was already in front of me leading the way through the tall grass when it happened.

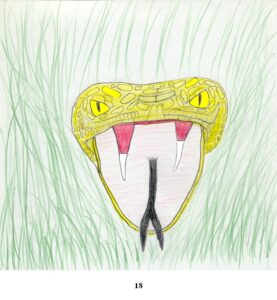

A shrill sound filled my ears followed by a sharp rattle.

Rattlesnake!!!

The snake rattle you hear on TV doesn’t do this unique serpent sound justice. The viper was 10 feet away, and I could see his head as it swayed above the thick grass.

The diamondback warned us not to come closer.

This was his domain.

Cassius disputed the snake’s claim to the land.

The misguided reptile would learn this was dog country now. The hair on the hunter’s back bristled, a sign that the fearless canine was angry and ready to fight.

Cassius ran around the snake. He barked ferociously. The dog bobbed and weaved and feinted, just like a boxer searching for an opening.

The snake’s rattles screamed, which was usually good enough to scare away potential opponents.

The serpent’s head cocked and then struck at the circling dog, but Cassius deftly dodged the bite and countered with a swift nip of his own. The dog had to be careful; he sensed his opponent’s dangerous efficiency when the serpent’s head buzzed past him and missed by a fraction of an inch.

At last, the dog thought, a challenge worthy of the mighty hunter.

The dog was so caught up in his dance of death with the diamondback that he didn’t hear me yelling his name.

Cassius jumped at the snake, and the snake struck at him. The dog nimbly sidestepped the speeding head that targeted him with its deadly ivory fangs.

I was terrified.

“WOOF! WOOF! WOOF!” the hunter, now the fighter, barked at the menacing creature. The dog knew the snake was dangerous to me, so as long as I stayed, he would protect me.

I realized there was only one thing to do. I bolted toward the camp, praying the dog would follow.

I yelled, “SNAKE! SNAKE! RATTLLLLLESNAAAAAAAKE!” as I ran.

Once I left the area, Cassius figured he didn’t really need to kill the snake after all. No telling what kind of trouble I would get into without him, the protector in him reasoned. He turned from the diamondback and sprinted after me.

The thankful snake slithered away. He was grateful he didn’t have to kill the courageous dog, though it did resemble the coyote, and he despised coyotes.

The dog passed me on the way to camp and led me in.

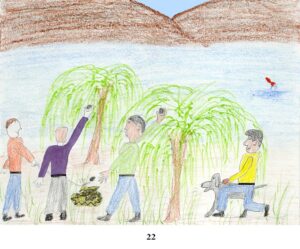

My elders armed themselves with sticks, except John, who unfolded his green Army shovel. We ran to find the snake.

The reptile was gone, but the dog, whose primary strength was his nose, quickly picked up the stealthy rattler’s scent and led us to him.

Cassius tried to charge the snake, but I grabbed the dog as he ran by, and I restrained him. I wasn’t about to let him near that rattler again lest the snake get lucky this time and plunge his venomous fangs into the hunter.

The guys threw rocks at the bewildered viper. They harassed the coiled and striking snake.

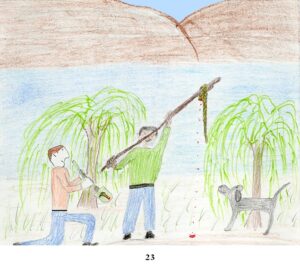

WHAM!

Denis, who was Joe’s best friend, struck the snake a solid blow to the head with a hefty rock. That stunned the viper, and the attackers ran in for the kill. They struck the reptile with their long sticks until the unfortunate snake was disoriented and couldn’t react when John rushed in and severed his head with the shovel.

John cackled madly as he scooped up the head with his shovel and showed off his fanged trophy. Joe picked up the snake’s body with his stick and held it aloft. He whooped like an Indian on TV.

I let the dog loose.

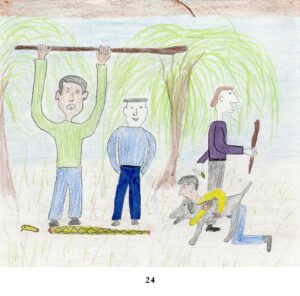

My brother and his friends weren’t finished mutilating the snake. Denis cut off the rattles and claimed them as his souvenir.

The dog was disappointed that he hadn’t killed the reptile. After all, he was king of the wild. So he charged at the dead reptile and tried to bite its severed head.

I recaptured the hound because I had heard stories of rattlesnakes striking even after they were dead. I feared the dog would be injured if I allowed him to chew on the dead snake’s head. Cassius couldn’t escape my strong hug, so he had to content himself with a furious wag of the tail and some vicious barking.

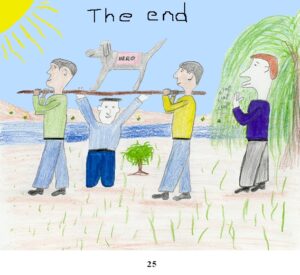

Cassius was the hero. He found the rattler. The confrontation with the snake was the apex of our adventure, so we showered the dog with treats, compliments, affectionate pats on the head and scratches behind the ears.

The dog reveled in our praise and graciously accepted his due. Despite his bravery, the dog knew he had met his match that day. Nevertheless, as far as we were concerned, the hunter forever retained his title of king of the wild.

The End

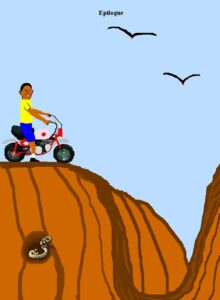

Epilogue

So that’s the story. I must admit that I am ashamed of what we did to that diamondback. We killed one of God’s creatures. That was the crime. It was a crime against nature.

The rattlesnake meant us no harm. He wanted only to live free, just as we yearned to live free, and he fought bravely to survive. By depriving the rattler of his life, we abused that rare two-day gift of freedom our parents had given us.

You may say that it was just a snake we killed, so get over it. I know that some snakes are cantankerous and dangerous, and they can strike you and kill you. To encounter a snake in the wild though, is a rare and wonderful gift. If it happens to you, consider yourself blessed, and don’t kill the snake. Admire it from a safe distance.

The snake is critical in maintaining the balance of the earth.

Without the snake, the rodent would be king of the wild.

Think about that.

David Madrid

© 2006 FabulousFables.com

Email: David Madrid